LEARN MORE: Smithsonian Magazine

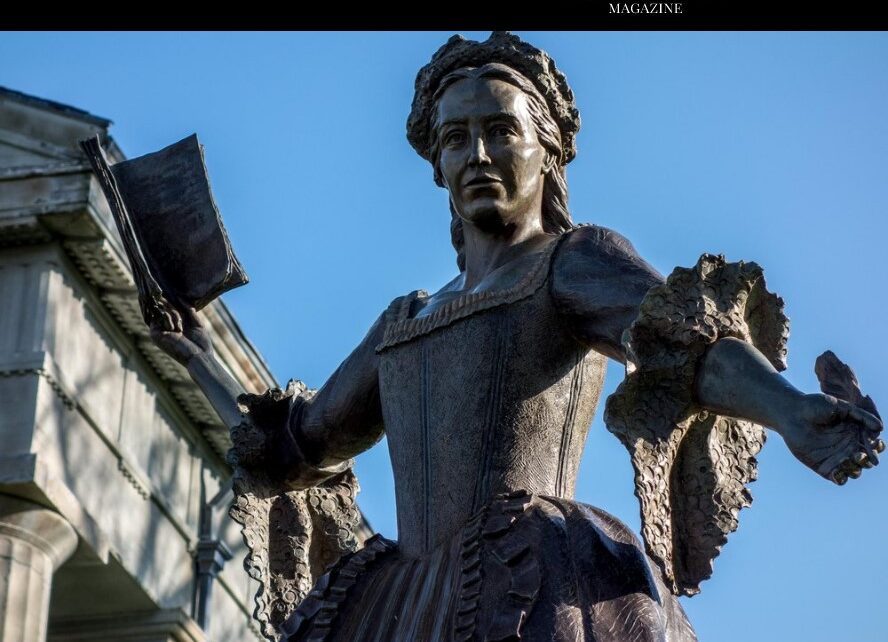

Mercy Otis Warren used her wit to agitate for independence.

John Adams and some of the other leaders of the American Revolution knew Mercy Otis Warren’s secret. At a time when few women could, Warren contributed her own voice to the cause for freedom. Her piercing satires of British authorities, published in Boston newspapers starting in 1772, had prepared colonists for the final break with the mother country. Adams called her the “most accomplished woman in America” – though he, too, would later feel the sting of her pen. Other Founding Fathers also celebrated her writing when she began publishing under her own name in 1790. A poet, playwright and historian, she’s one of the first American women who wrote mostly for publication.

The younger sister of James Otis, Boston’s leading advocate for colonists’ rights in the 1760s, Mercy was a bookish girl in a time when many girls never obtained basic literacy. Her father, James Sr., encouraged her curiosity. She demanded to join in when her brothers read aloud and took the place of her second-oldest brother during lessons with their uncle, a local minister. While James was a student at Harvard, he’d come home and tell her about his studies, especially the political theories of John Locke. She read voraciously: Shakespeare and Milton, Greek and Roman literature, Moliere’s plays in translation, Sir Walter Raleigh’s History of the World. At age 14, she met her future husband, James Warren, at her brother’s Harvard graduation. They married in 1754 at ages 26 and 28, respectively. While raising five children, she began writing private poems about family and nature.

In the 1760s, the Warrens’ Plymouth home became a meeting-place for like-minded patriots. Her husband joined her brother in the Massachusetts legislature—together, they opposed colonial governor Thomas Hutchinson. But James Otis’ career was cut short in 1769, when a British customs officer bashed his head with a cane in a bar brawl and the trauma pushed him into mental illness.

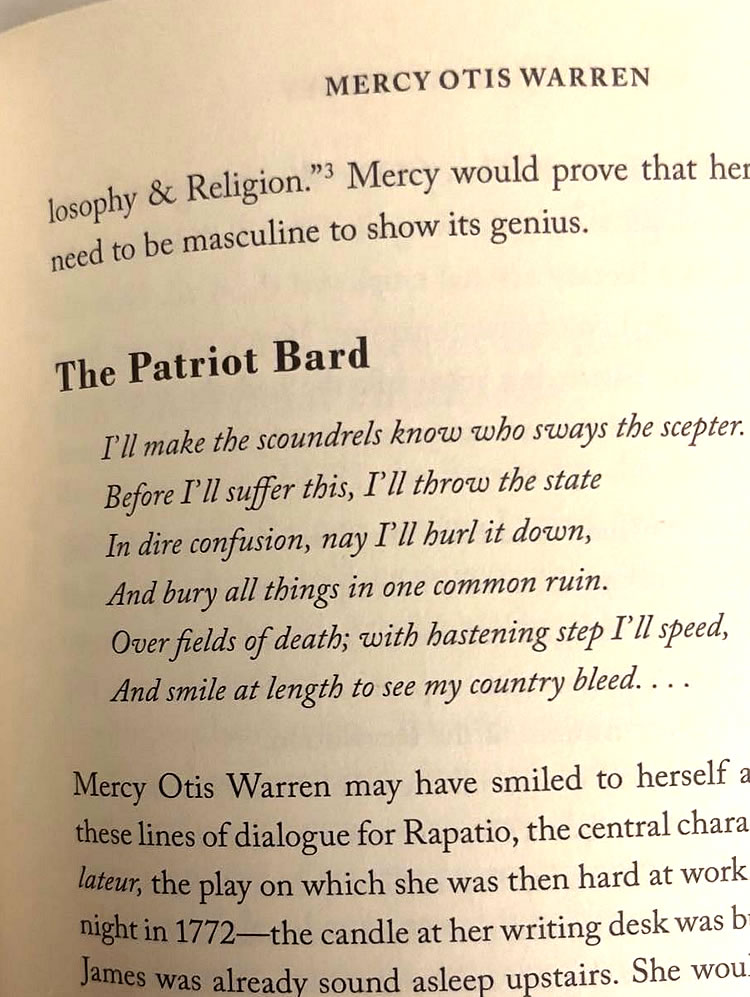

After Otis went mad, his sister began answering his correspondence, including letters from radical British historian Catharine Macaulay. Encouraged by her husband, who praised her “genius” and “brilliant and busy imagination,” Warren also began writing satirical plays that attacked Hutchinson, her brother’s nemesis. Her first play, The Adulateur, published in Boston’s Massachusetts Spy newspaper in March and April 1772, portrayed a thinly disguised Hutchinson as Rapatio, the dictatorial leader of the mythical kingdom of Servia. Warren pitted Brutus, a hero based on her brother, against Rapatio. “The man who boasts his freedom,/Feels solid joy,” Brutus declared, “tho’ poor and low his state.” Three years before the Revolution, Warren’s play warned that a day might come when “murders, blood and carnage/Shall crimson all these streets.”

The Adulateur caught on with Boston’s patriots, who began to substitute its characters’ names for actual political figures in their correspondence. Then, in 1773, Boston newspapers published private letters of Hutchinson’s that confirmed patriots’ worst suspicions about him. (In one, Hutchinson called for “an abridgement of English liberties in colonial administration.”) Warren responded with The Defeat, a sequel to The Adulateur, which cast Rapatio as the “dangerous foe/Of Liberty of truth, and of mankind.”

Leading patriots knew Warren was the play’s anonymous author. After the Boston Tea Party, John Adams asked her to write a mythical poem about it, as “a frolic among the sea-nymphs and goddesses.” Warren obliged, quickly writing “The Squabble of the Sea-Nymphs,” in which two of Neptune’s wives debate the quality of several teas, until intruders poured “delicious teas” into the water, thus “bid[ding] defiance to the servile train,/The pimps and sycophants of George’s reign.” In early 1775, as Bostonians chafed at Britain’s Intolerable Acts, Warren published poems that encouraged women to boycott British goods. Another play that mocked loyalists, The Group, was published two weeks before the battles of Lexington and Concord.

Like other patriot writers, she insisted on anonymity to avoid British retaliation, telling one publisher not to name her “so long as the spirit of party runs so high.” Anonymity may have also helped her as a female writer, by insuring that readers judge her work on its merits, not dismiss it because of her sex.

During the war, Warren worked as her husband’s personal secretary and managed their Plymouth farm while he was away governing as president of the Massachusetts provincial congress. She kept up a frequent correspondence with John Adams, a protégé of her brother’s, and his wife, Abigail. In November 1775, as the British held Boston under siege, James Warren wrote to Adams, a friend and delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, urging him to give up on trying to reconcile with George III. “Your Congress can be no longer in any doubts, and hesitancy,” he wrote in his lawyerly style, “about taking capital and effectual strokes.”

Mercy insisted on adding a paragraph of her own. “You should no longer piddle at the threshold,” she dictated. “It is time to leap into the theatre to unlock the bars, and open every gate that impedes the rise and growth of the American republic.”

As Americans debated the proposed new Constitution in 1787, Warren and her husband became Anti-Federalists. As part of the older generation of revolutionaries that had emerged from provincial governments, they were more loyal to their state than the federal government. Both Mercy and James penned arguments against the Constitution – published anonymously, much like the Federalist Papers. Her essay, published in 1788 under the pseudonym “A Columbian Patriot,” warned that the Constitution would lead to “an aristocratic tyranny” and an “uncontrolled despotism.” The Constitution, she warned, lacked a bill of rights – no guarantees of a free press, freedom of conscience, or trial by jury. Warren complained that the Constitution didn’t protect citizens from arbitrary warrants giving officials power to “enter our houses, search, insult, and seize at pleasure.” Her sweeping, florid essay proved more popular than her husband’s narrow, precise legal argument. It contributed to the pressure that led Congress to pass the Bill of Rights in 1789.

Warren shed her anonymity in 1790, publishing her book Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous under her own name. It collected two decades of her work, including Revolutionary-era satires and two new plays with prominent female characters. Adams and George Washington sent congratulations; Alexander Hamilton proclaimed her a “genius” of “dramatic composition.” But the compilation was just a prelude to her masterwork.

In 1805, Warren published a three-volume, 1,200-page history of the American Revolution. Titled History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, it made her the U.S.’s first female historian, and the only one of her era to write about the nation’s founding from an Anti-Federalist and Jeffersonian Republican perspective. The book sold poorly—and provoked a vicious series of letters from John Adams, who had encouraged her to start the history. His Federalist politics had clashed with hers, and he didn’t come off terribly well in her telling. “History is not the province of the ladies,” Adams sniped in a letter to a mutual friend.

History disagrees. Filled with character insights, primary sources, and footnotes, Warren’s History is still useful and insightful to modern readers. It’s “one of the earliest and most accurate histories of the independence movement,” wrote Rosemarie Zagarri in her biography of Warren. “The work conveyed a sense of grandeur, intellectual ambitiousness and moral integrity that impresses even today.”

LEARN MORE: Smithsonian Magazine